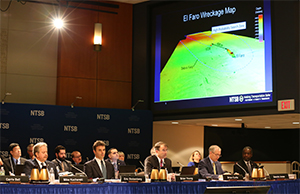

El Faro Capt. Michael Davidson should have done more to avoid Hurricane Joaquin, and after the ship lost propulsion he should have prepared crew sooner to abandon the crippled vessel, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined.

Davidson also erred by dismissing junior officers’ suggestions to change course hours before the ship sank. Taken together, his actions put the ship and crew at risk, the NTSB said in findings released Dec. 12.

“I don’t think he wanted to sail into the hurricane. I don’t think he wanted the ship to sink,” NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt said during a Dec. 12 hearing in Washington, D.C. “He … had a mental model that the hurricane would be in one place, and based on that mental model and based on his previous experience he thought they were going to be OK.”

The agency also cited TOTE Maritime, owner of the container/roll-on/roll-off cargo ship (con-ro), for crew training failures and an inadequate safety culture. Investigators suggested TOTE put implicit pressure on Davidson that could have influenced his decisions.

|

|

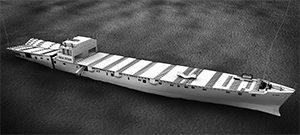

A computer-generated illustration shows El Faro as it rests on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. The hull is largely intact. The pilothouse is missing the bridge deck and the deck below it, as well as the main mast and exhaust stack. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

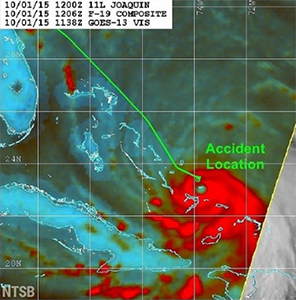

All 33 crewmembers died when El Faro sank at about 0740 on Oct. 1, 2015, some 40 miles from Crooked Island in the Bahamas. The vessel encountered 75-mph winds and 30-foot waves as it approached the hurricane while sailing from Jacksonville, Fla., to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The NTSB spent 26 months investigating the incident, which is considered the worst for a U.S.-flagged ship since SS Poet disappeared in 1980. The agency issued 81 findings and 53 safety recommendations in the El Faro case. Many are similar to those included in the U.S. Coast Guard report issued in October.

The NTSB’s 400-plus-page report wasn’t out by press time, but the 81 findings offer the clearest picture yet about what happened aboard the con-ro and what caused it to sink.

Investigators believe Hurricane Joaquin’s winds caused El Faro to heel to starboard early on Oct. 1. The list worsened after seawater that pooled inside the leaning ship’s semi-exposed second deck flowed down an open scuttle into cargo hold No. 3.

As water levels rose in hold No. 3, improperly lashed vehicles eventually broke free and started floating. The NTSB believes one or more vehicles ruptured unprotected fire main piping, causing rapid flooding that “significantly compromised the vessel’s stability.” Bilge pumps couldn’t keep up with the rising water.

During El Faro’s final 40 minutes afloat, more water likely entered through ventilation ducts in the hull leading to the cargo holds. Watertight baffles in the ducts were left open on the final voyage.

The NTSB and Coast Guard reached similar conclusions about the cause of El Faro’s engine failure at about 0613 on Oct. 1. Both believe the loss of lube oil pressure caused the plant to shut down.

Davidson induced a port list at about 0545 amid concerns about how the starboard lean could affect the propulsion system. Ultimately, this led to the engine failure, Sumwalt said.

|

|

This graphic shows El Faro’s track line in green as the ship sailed from Jacksonville, Fla., to Puerto Rico on Oct. 1, 2015. Color-enhanced satellite imagery from close to the time the ship sank shows Hurricane Joaquin in red, with the storm’s eye just to the south of the accident site. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

Investigators learned El Faro frequently sailed with lower than recommended lube oil levels. Its lube oil suction tube was located slightly to the starboard side of center. With the ship leaning heavily to port and rolling in the waves, air likely entered the bellmouth of the suction pipe.

The NTSB determined crew likely weren’t aware of potential propulsion issues stemming from “sustained excessive list” and suggested TOTE should have provided that information to engineers. El Faro carried more than enough lube oil that could have been added to keep the suction pipe submerged even during extreme lists.

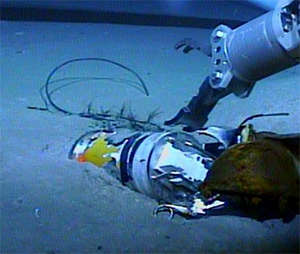

Much of what the NTSB and Coast Guard learned about the final voyage came from El Faro’s voyage data recorder (VDR) found about 15,000 feet under the surface. From that recording, investigators know Davidson and his chief mate discussed the hurricane on Sept. 30 and charted a course to avoid it.

But the storm track changed over the next 12 hours, and junior officers on watch overnight recognized El Faro was heading straight toward Joaquin. Davidson rejected the third mate’s suggestion to change course before midnight on Sept. 30, and about two hours later he dismissed a similar request from the second mate. Davidson was off the bridge from about 2000 on Sept. 30 to 0400 on Oct. 1.

|

|

A photo presented by the NTSB on Dec. 12 shows El Faro moored without cargo, with “running rust” visible on its hull plating. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

The captain’s failure to consider these requests, the NTSB found, endangered El Faro and its crew. Yet board members also determined that the two junior officers should have been more explicit with their concerns. Ultimately, the board found bridge resource management concepts weren’t followed.

“This is not about blame, this is about making sure future generations of mariners understand … you’ve got to get their attention,” Sumwalt said, referring to junior officers clearly addressing concerns to their superiors.

The VDR transcript reveals how conditions on the ship worsened during its final hour afloat. By 0713, there was talk of the fire main rupturing and cars floating in the No. 3 hold. Davidson rang the general alarm at 0727 and followed with an abandon-ship order two minutes later. By then, the NTSB said, crew probably had little chance of survival.

Even so, the NTSB determined El Faro’s open lifeboats would be difficult or impossible to launch during a hurricane. The agency recommended that other cargo ships with open lifeboats replace them with enclosed lifeboats “that adhered to the latest safety standards.”

Investigators said TOTE’s safety management system was inadequate, and that the plan lacked procedures for maintaining watertight integrity and responding to heavy weather or emergencies. Various training shortcomings also were identified. For instance, Davidson was exempt from training courses in heavy weather operations.

“The company’s lack of oversight in critical aspects of safety management, including gaps in training for shipboard operations in severe weather, denoted a weak safety culture in the company and contributed to the sinking of El Faro,” the NTSB determined.

TOTE President and CEO Anthony Chiarello declined to comment following the Dec. 12 hearing. Later that day, the company issued a statement promising to “carefully study” the Coast Guard and NTSB findings.

“We as a company intend to learn everything possible from this accident and the resulting investigations to prevent anything similar from occurring in the future,” the statement said.

|

|

A hydraulic arm from the Navy’s CURV-21 remotely operated vehicle reaches for El Faro’s voyage data recorder 15,000 feet below the surface of the ocean. The VDR was recovered on Aug. 8, 2016, capping a 10-month multi-agency effort. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

Maritime lawyer William Bennett, who represents Davidson’s widow, disputed key aspects of the NTSB findings, including criticism of Davidson’s bridge resource management. He said the conditions that the ship encountered should not have caused it to sink.

“Based on all of the evidence that was presented in this case,” Bennett said, “it is clear that there was no single primary cause for the sinking — rather it was a combination of many unfortunate contributing factors.”

Glen Jackson, whose brother Jack Jackson died in the accident, said the end of the government’s investigation offered little in the way of closure.

“My brother is dead,” he said, “and I am going to miss him until the day I die.”