A containership collided with an oncoming articulated tug and barge (ATB) near the Bayonne Bridge in thick fog after the tugboat couldn’t avoid the ship while making a turn during a flood tide, according to documents released by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

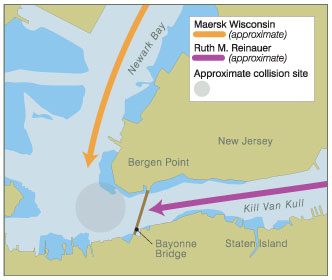

The accident involving the box ship Maersk Wisconsin and the tug Ruth M. Reinauer happened at 0215 on Dec. 5, 2011, at Bergen Point. N.J. The 958-foot ship had departed Port Newark and was southbound in Newark Bay approaching Kill Van Kull, and the tow was westbound in Kill Van Kull pushing a tank barge in ballast.

Maersk Wisconsin was preparing for a turn to port at Bergen Point, while the oncoming Ruth M. Reinauer was turning to starboard with the empty 390-foot barge RTC 102.

The ship was sailing at about 3 knots, according to Automated Information System data from PortVision. The 4,720-hp tug was making 6 knots.

At the time Maersk Wisconsin undocked at 0110, visibility was five miles, but it deteriorated after that, according to documents released by the NTSB. The pilots reported that visibility was reduced to “zero” by the time of the Bergen Point approach. Fog signals were sounded and sécurité calls were issued.

Because the docking pilot aboard Maersk Wisconsin was giving commands and communicating with his assist tugs, the Sandy Hook pilot handled radio communications with the oncoming tow. He asked Ruth M. Reinauer if it could hold up while the ship negotiated the turn and transited the Bayonne Bridge.

“The Ruth’s response was that he was already off Bayonne city dock and couldn’t,” the Sandy Hook pilot reported to the NTSB. “I couldn’t verify his position without changing the scale of the computer screen which I was reluctant to do at this critical point of our turn. We were just about dead in the water heading east toward the Bayonne Bridge off Bergen Point when the Ruth Reinauer called and said that he wasn’t going to make his turn to avoid us. We sounded the danger signal, backed full astern and evacuated the bow. … The Ruth Reinauer struck our bow.”

Ruth M. Reinauer’s mate was on watch, operating the vessel. He said the ship’s pilot asked him to stay close to the red buoys marking the north edge of the channel. When the tug’s mate finally could see Maersk Wisconsin, the ship was too far over into the tow’s path, he said. The mate could see only the green running lights on the starboard side of the box ship.

“I did not see Maersk Wisconsin’s red running light, which would have been on her port side, and which I should have seen in a normal passing situation,” the mate told investigators. “This indicated to me that she was out of shape. I continued to turn hard to starboard. As I continued to turn to starboard, it appeared Maersk Wisconsin was turning to her port and was getting closer to us. I spoke to the pilot again, and informed the pilot words to the effect that he had to do something, and that he had to use his assist tugs to move his vessel away from us. The pilot responded that she was dead in the water, and not moving. I believe I stated to the pilot that his vessel was moving.”

The mate said he attempted to back down the tug, but the ship’s bow struck the barge on its port side.

“The stem of Maersk Wisconsin made contact with the barge, and when contact occurred Maersk Wisconsin was on our side of the channel, and was out of shape,” the mate said. “It appeared Maersk Wisconsin had started to make its turn to port too soon and its bow may have gotten pushed toward the northeast by the flood tide. However it happened, Maersk Wisconsin made contact with RTC 102 on our side of the channel, and was in a position which indicated it was completely out of shape. Maersk Wisconsin had plenty of room to stay clear of our tug and barge.”

The tug’s master, who went to the wheelhouse after feeling a shake, testified that the containership was out of shape and was over on the tug’s side of the channel. The master of the U.S.-flagged Maersk Wisconsin disputes that account. A lookout notified him that the tow encroached into the ship’s side of the channel.

“The bow reported that a collision situation existed, that the tug was crossing the channel toward the south. I gave the order to evacuate the bow, and sounded the danger signals. The engine was placed to full astern,” the master told the NTSB.

“At 0212 the speed of our ship was near zero if not going astern,” he said. “The inbound tug continued to cross our bow port to starboard and contact was made. We were in our proper position in relation to the channel during the entire maneuver.”

RTC 102’s port-side ballast tanks No. 3 and 4 were holed above the waterline, its deck top had a large dent and railings were smashed. Maersk Wisconsin had dents in its starboard bow area.

The docking pilot attributed the accident to “excessive speed in fog by the Ruth Reinauer and failure of the Ruth Reinauer to hold back for large outbound ships.”

The forward draft of Maersk Wisconsin was 43 feet 10 inches. The draft was only 41 feet aft.

The Sandy Hook pilot noted that, during the exchange at Port Elizabeth, both pilots “commented on the ship’s unusual draft forward compared to the draft aft to the ship’s master. It wouldn’t be a problem draftwise because of the flood or rising tide that we would have the entire transit, but the shiphandling would be much slower to respond.”

Maersk Wisconsin is operated by Maersk Line Ltd. of Norfolk, Va. The operator of Ruth M. Reinauer and the barge is Reinauer Transportation Cos. of Staten Island, N.Y.

The accident happened in a regulated navigation area. Neither the NTSB nor the Coast Guard released radio transcripts or any statements from the Vessel Traffic Service. The Coast Guard said its investigation was continuing in August.

Reinauer Transportation officials declined to comment. An inquiry to Maersk Line was referred to the company’s U.S. offices, which didn’t respond.