J.W. Herron began pushing into a bank of the Mobile River when the captain realized the towboat’s starboard propeller wasn’t turning. Moments later, he saw the engineer running toward the wheelhouse, yelling and gesturing toward the exhaust stacks.

The captain and engineer walked aft to investigate black smoke billowing from the engine room. The engineer peered through an engine room window and saw the back of the port-side engine aglow.

The fire started at about 1340 on Dec. 13, 2017, when the vessel was eight miles north of Mobile, Ala. For the next 70 minutes, the fire spread through the 3,000-hp towboat. Total damage reached $1.5 million. No one was injured and no pollution was reported.

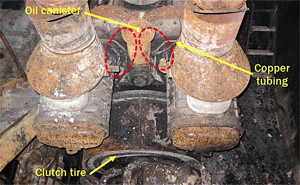

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that leaking lube oil from a propulsion engine hose or tubing fitting ignited. The exact source of ignition could not be found, although investigators believe it was either a hot engine surface or slipping clutch.

“Contributing to the severity of the fire was the location of the emergency engine shutdowns and fuel supply shutoffs near the exterior engine room doors, which proved to be inaccessible,” the agency said in its accident report. Another contributing factor was the crew’s inability to close off the air supply to the engine room, which allowed the fire to grow and spread throughout the vessel, the NTSB said.

The 50-year-old J.W. Herron, operated by Four Rivers Towing of Murray, Ky., left Three Mile Dry Dock and Repair in Mobile three hours before the fire. Crew later assembled an eight-barge tow with seven empty hopper barges and a deck barge. The 88-foot J.W. Herron also towed the 45-foot shift boat Dana Jean.

Crew told investigators that J.W. Herron’s mechanical systems worked fine during the 90-minute transit to Twelvemile Island on the Mobile River. That said, there were two clutch incidents in the weeks before the fire. According to the NTSB report, one incident occurred around Nov. 20 when the starboard engine abruptly increased in rpm. About three weeks later, the vessel “smoked a clutch tire” after the starboard prop hit a log.

Upon arrival at Twelvemile Island, the captain landed the tow’s aft end on the east side of the bayou and crew later brought Dana Jean alongside J.W. Herron. Next, the captain repositioned J.W. Herron to push the port lead barge into the bank.

He placed both engines ahead at idle speed but noticed no forward movement. After increasing power to 500 rpm, the captain looked aft and saw calm water behind the starboard prop. At about this time, 1340, the deck hand and engineer working on the barges noticed “dark black smoke” coming from the stack fan outlet.

The captain and engineer investigated the fire from the forward starboard engine room window, where the engineer noticed a “glow” between the port engine and its gearbox.

The deck hand and engineer boarded Dana Jean and moved it away from the burning towboat. Meanwhile, the captain activated a remote fuel shutoff for the starboard engine and generators but could not reach the shutoff for the port-side engine and genset due to the thick smoke. These shutoffs were located on the port and starboard sides near forward engine room windows, the report said.

Local firefighters reached the burning vessel at about 1510, at which time the fire was winding down, the captain told investigators.

The captain cited the slipping clutch as a possible cause of the fire, a point echoed by the engineer, who noted the lack of oil in the engine’s gear-driven air blower as another possibility. The engineer told investigators that in the past, engine vibrations had loosened copper tubing flare fittings that “wept” oil — although he resolved the problem by tightening them. One such copper tube supplied lube oil to air blowers above the clutch.

A forensic firm hired by the towboat’s insurers reached a different conclusion. The firm found that “the fire occurred near the aft end of the starboard engine, likely from a ruptured hose on the vacuum canister that would have sprayed lube oil throughout the engine compartment and onto hot engine surfaces and the clutch tire, thus igniting the oil.”

Oxygen continued to feed the fire once it started. Crew could not shut off the engine room supply and exhaust fans because the controls were located in the engine room. Engine room exhaust vents on the aft side of the stacks remained open because the fixed louvers could not be closed. Engine room doors and windows also were open.

Controls for the fire pump were located inside the engine room, which was not equipped with a fixed fire suppression system. Such a system was not required, the NTSB said.

|

|

The aft side of J.W. Herron's starboard engine with red circles indicating where stainless-steel braided rubber hoses were missing after the fire. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

J.W. Herron had twin 1,500-hp GM 12-645 EMD diesel engines and Falk reduction gears. Operators performed maintenance “in house,” but those records — reportedly stored on the towboat — were lost in the fire. The captain said fire drills were conducted about once a month, although some of these records also were destroyed.

Urine testing immediately after the incident showed the engineer tested positive for methamphetamine. It could not be determined when he ingested the drug, and there was no indication it impaired him during the voyage or fire response. The NTSB still emphasized that “any drug use by a crewmember poses a safety hazard while on board a vessel.”

Graestone Logistics owned J.W. Herron but Four Rivers Towing operated it through bareboat charter. According to the NTSB, J.W. Herron’s captain at the time of the incident was a co-owner of Three Mile Dry Dock, a firm listed on Graestone’s website.

Graestone did not respond to a request for comment, and details of any arrangement with Four Rivers Towing could not be confirmed. Four Rivers also could not be reached for comment.