The U.S. Coast Guard has embarked on a multiyear study aimed at creating harmony and order among the many interests vying for limited space along the increasingly busy coastline.

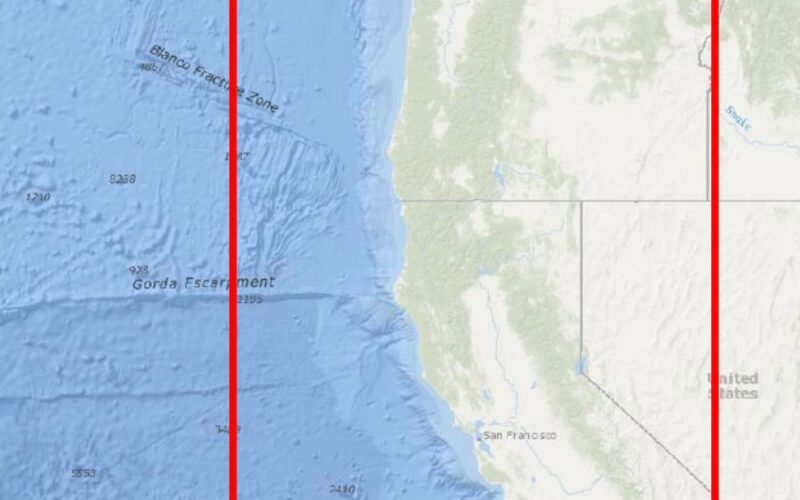

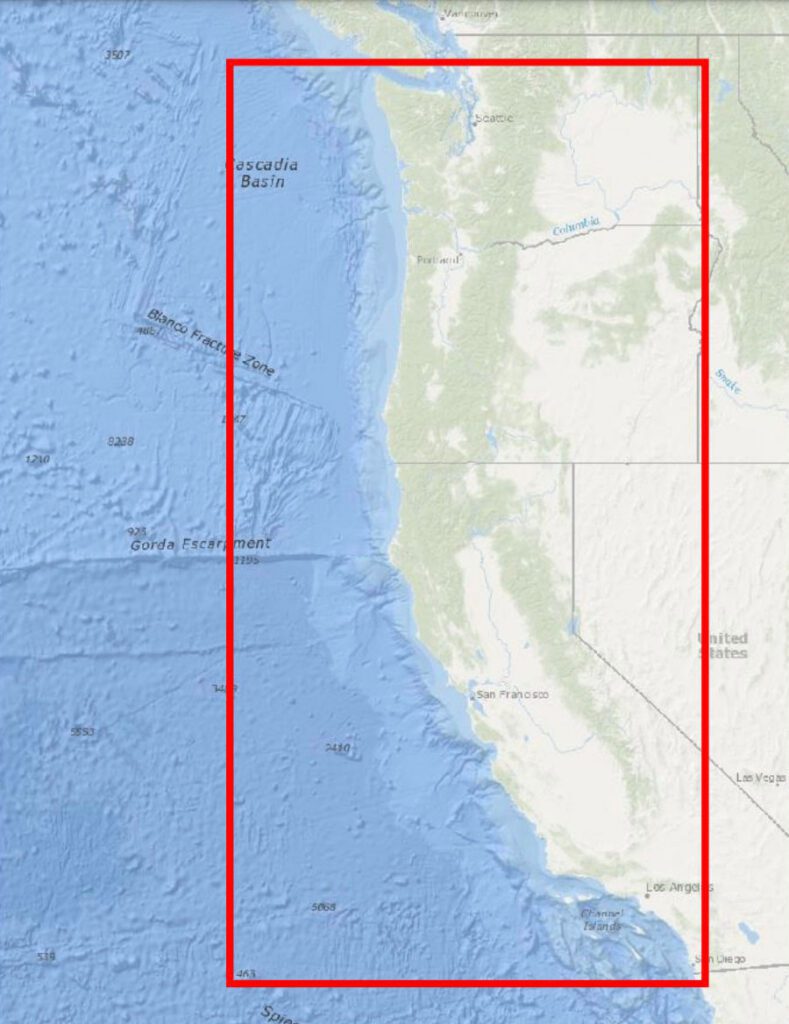

The Pacific Coast Port Access Route Study (PARS), which began in 2021, intends to obviate potential navigational challenges before they become problems. Its authors looked at traffic patterns to understand what changes may be needed as the waterways fill with more stakeholders beyond shipping.

These potential users include aquaculture, offshore wind power, fishing grounds and even space launch and recovery operations. Unchecked growth of these non-maritime activities could create congestion and pressure, creating the potential for collision and other problems.

“Under the Ports and Waters Safety Act, the Coast Guard is directed to conduct a study if and when there is a need, and evaluate what the current trends are,” said Tyrone Conner, deputy chief of Waterways Management for the 11th Coast Guard District. “We want to find out what is the risk and how to mitigate the risk. There are certain things the Coast Guard can do.”

What the Coast Guard did was recommend, in draft form, a series of voluntary changes to create some order for different uses and operations.

Rule changes would create a fairway 15 nautical miles wide that follows current vessel traffic patterns along the coast and connects with existing traffic separation schemes at the Strait of Juan de Fuca, San Francisco, Santa Barbara and Los Angeles-Long Beach.

The plan also would create a nearshore fairway north of San Francisco that is five nautical miles wide and establish a Coastal Fairway Zone that overlies the existing D13 Crabber-Towboat Lanes along the coast.

The study recommends removing the International Maritime Organization’s recommended routes located offshore of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary in California, and continuing with the existing voluntary practice of keeping bulk chemical and petroleum carriers at least 50 nautical miles offshore without charted lanes.

To get to these recommendations, the Coast Guard studied the traffic patterns of the last 10 years using Automatic Identification System (AIS) data to spot the busiest legs of ship channels. The service also solicited input from anyone with an opinion or concern in the matter. This included federal, state and tribal authorities, as well as operators of maritime businesses and research organizations in the target zone of the study along the entire Pacific Coast.

“The comments we’ve received have helped us with honing some areas,” Conner said. “We were able to get a lot of good feedback.”

Many comments tried to remind the Coast Guard of the mortal danger ships can pose to whales and other marine life.

“We would like to achieve both wildlife and human safety at the same time,” Jaimie Jahncke, director of California Currents, parent of Point Blue Conservation Science in Petaluma, Calif., said in an interview. To this end, Jahncke said, Point Blue would like shipping routes as far out to sea as possible, and the pathways from those lanes to the ports to be as short as possible.

“A simple solution could help decrease the number of whales killed by ships: move vessel traffic away from the shelf,” Point Blue wrote in its comment. “Whether to consider an offshore shift in traffic or other approaches, we strongly encourage the PARS process to account for the best available science and habitat use predictions for marine mammals and turtles that are susceptible to vessel collisions, especially large whales.”

The Pacific Merchant Shipping Association urged the Coast Guard to consider aquaculture and other offshore projects in its thinking.

“While the California aquaculture effort is in its infancy and no sites have been formally proposed, an opportunity study has been published by NOAA, identifying 10 potential areas in federal waters offshore Santa Monica and north to Santa Barbara,” the association said in its comment. “It is important to note that the Port of Hueneme is located very close to a cluster of identified sites and the farm(s) may push waterway users out into newly determined or traditionally utilized vessel lanes.”

Others addressed the new and expanded uses that the seaboard will host — if it isn’t doing so already.

“At this time, we do not have much objection to the planned routes,” Russell Shrewsbury, vice president of Western Towboat Company, based in Seattle, said in an email.

“I think the hard part is going to be the development and implementation of floating offshore wind farms on a coast that can see some significant weather systems,” he continued, “We don’t think it’s out of the realm of technology, but having more obstructions off the coast with a semi-submersed power cable will be interesting.”

Comments for the PARS study closed on Nov. 9, 2022. Next steps will be for the Pacific command to sign off on the recommendations, which will then to go Coast Guard headquarters to begin rulemaking. That effort will contain its own opportunities for public engagement.

This process normally takes from two to five years from start to finish, Conner said. The study will be published on NAVCEN’s website, www.navcen.uscg.gov.