Capt. Jim Harkin had just finished explaining the attributes of the repowered Cape May-Lewes Ferry New Jersey when he heard the familiar sound of a car alarm on the main deck.

He paused for a moment while his pilot, former ferry system captain Tom Lippincott, tried to locate the owner of a white Mercedes with New Jersey tags. Luxury cars, it turns out, are particularly sensitive to the ferry’s motions.

“It can be annoying for the people down there when those things go off,” Harkin said as the horn abruptly stopped honking.

The occasional car alarm is par for the course on New Jersey, which with Cape Henlopen and Delaware make up the Cape May-Lewes Ferry fleet. The 100-vehicle ferries cross Delaware Bay between Lewes, Del. (pronounced Loo-is), and Cape May, N.J., up to 20 times a day during the summer months.

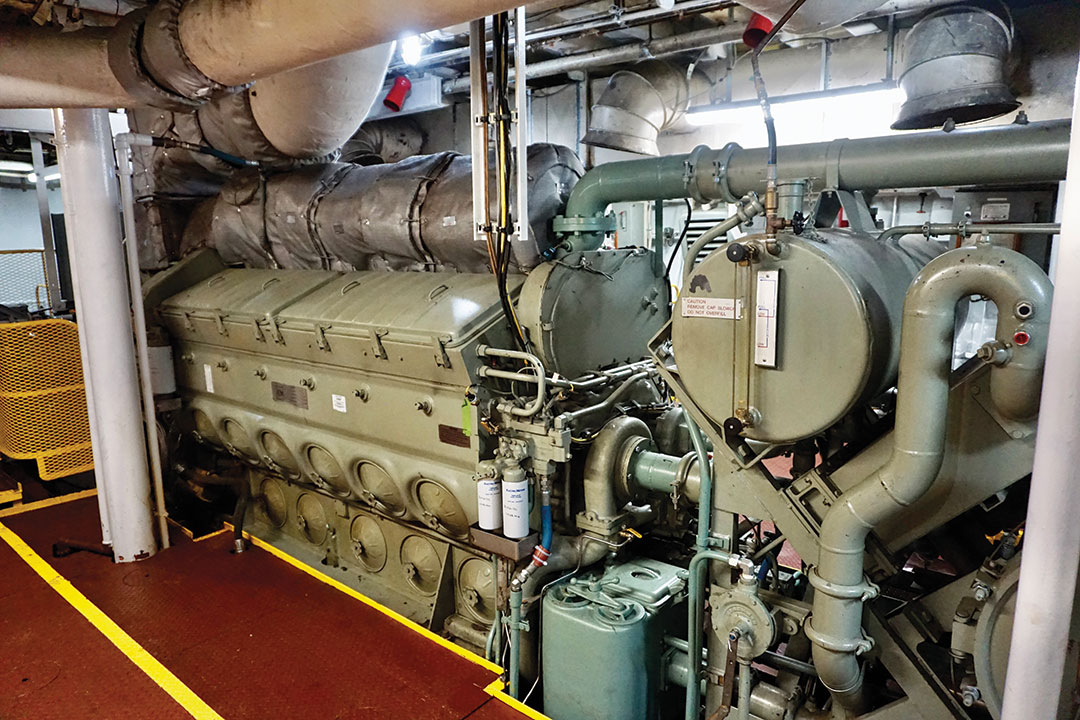

The 47-year-old New Jersey recently underwent a $20 million overhaul and repowering at Caddell Dry Dock and Repair Co. in Staten Island, N.Y. The shipyard replaced the ferry’s World War II-era Fairbanks Morse main engines with 3,000-hp EMDs that meet EPA Tier 3 emissions standards.

Heath Gehrke, operations manager for the Delaware River and Bay Authority (DRBA), which operates the ferry, said the new engines reduce emissions by more than a third. They also will save about $130,000 a year in maintenance costs thanks to longer cycles between engine overhauls. Cape Henlopen is the only ferry left with Fairbanks Morse engines.

“It is becoming extremely difficult to get the parts, and even the technical assistance is somewhat limited,” Gehrke said. “We hoped we would be on a quicker track to newer vessels, but it looks like we have at least one more (engine) overhaul to do on the Henlopen. I hope that will be the last one.”

The DRBA received $3 million in federal funding toward New Jersey’s repowering. Other upgrades included extensive hull repairs and steel replacement, and renovations to the passenger areas and various internal compartments. The ferry returned to service last fall after nearly 11 months in the shipyard.

Back on New Jersey, Lippincott guided cars, trucks and large campers onto the vehicle deck with assistance from several deck hands. He worked for the DRBA for 30 years before retiring 12 years ago as a captain. Now 72, he works during the summer months as a pilot.

“It makes me feel good at my age to come out and work like this. I know my job, so when I come down here I know I can do a good job for the captain,” Lippincott said later. “Some loads are pretty challenging, but it seems like it works out.”

Harkin served 29 years in the U.S. Navy and joined the ferry service about a decade ago. He stood by as AB Jim Koenig steered the 320-by-68-foot New Jersey away from the Lewes terminal, located just east of Cape Henlopen State Park’s sandy beaches. The ferry made a swooping S-turn as it steered around a historic breakwater that dates back to the 19th and 20th centuries.

The structure, maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, created the Harbor of Refuge inside of Cape Henlopen for vessels that encounter bad weather in Delaware Bay. The breakwater is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the lighthouse on its southern end dates to 1926.

Harkin gave Koenig headings as New Jersey sailed to the south of the breakwater while the inbound Cape Henlopen approached Lewes to the north of the breakwater. Toward the northwest, off the port bow, deep-draft ships sat at anchor awaiting berths in Philadelphia or Wilmington, Del. Minutes later, the tugboat Genesis Valiant passed the ferry on the starboard side pushing a single barge.

Commercial and recreational traffic is one of the main challenges along the 17-mile crossing, most of which occurs in open water. Weather is another, particularly during the winter when fog and wind can create unforgiving conditions.

“When it’s blowing 40 to 50 (mph) out of the northwest, it’s a nail-biter. Probably the most fetch we have is the northwest,” Harkin said. “This time of year … has been great. This summer we have had a lot of smooth sailing.”

The Cape May-Lewes Ferry is operated by the DRBA, a quasi-governmental organization with representatives from New Jersey and Delaware. The DRBA also oversees the 71-year-old Delaware Memorial Bridge linking the two states over the Delaware River and four regional airports.

Ferry service between the two states began in 1964. Since then, more than 43 million passengers have ridden its vessels. Each year, the ferry system transports more than one million people and 275,000 vehicles. Summer, of course, tends to be busiest as vacationers head north to the Jersey Shore or south to Delaware’s beaches.

Some travelers take the ferry to avoid a busy stretch of Interstate 95, and others choose it to watch seabirds or search for dolphins and whales along the route.

Gauging the ferry system’s rebound from Covid-19 is not simple, in part because ridership fluctuates when a ferry is down for maintenance or in dry dock for an extended period. Still, Gehrke said vacation travelers have returned in earnest.

“What I will say is on the weekends, we have been adding departures and they are almost all sold out,” he said.

The DRBA plans to build at least one new ferry and potentially up to three if funding allows. Gehrke expects the initial vessel will be hybrid-ready, meaning it will be designed to accommodate batteries in the future. The power demands on an 85-minute ride and the availability of electricity in two overstretched power grids mean full-scale electrification is not feasible in the near term.

“We are trying to put charging infrastructure in place so we can run on battery power and maybe eventually 100 percent on battery power,” he said. “They are a little on the edge of the envelope, at least in the U.S., for the range we need. But the bigger limitation is getting the power we need.”

The DRBA is working on a master plan that would incorporate solar and wind power onto its terminal sites, creating some electricity for any future hybrid ferry. The quickest time frame for the first new ferry, based on the design, contracting and construction periods, is roughly three years.

Gehrke expects Elliott Bay Design Group of Seattle will design the new ferry under an expansion of an existing contract.

New Jersey continued its path to the northeast, meeting sister ferry Delaware on the way. Seabirds frolicked in New Jersey’s wake as it approached Cape May, home to world-class birdwatching. To the east, the Cape May Lighthouse stood above golden sandy beaches.

Harkin slowed the vessel to prepare for a starboard turn into the terminal, located on the west side of the Cape May Canal.

“We will get set real hard depending on the tide,” he explained, noting that the tide was ebbing with a current nearing 2 knots. “We can’t just go straight into the canal — we have to make an adjustment for the set.”

The vessel passed through a breakwater at the canal’s western edge and lined up for the landing. Harkin pulled back on the engines as the vessel made its final approach. Minutes later, the gate was open and vehicles made their way off the ferry one by one.

New Jersey tied up in Cape May for the night. But with another month of summer to go, more busy days lay ahead.