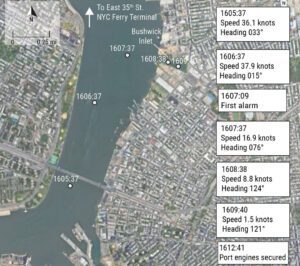

The Seastreak ferry Commodore was sailing up the East River at about 37 knots when alarms warned of a control failure in its two port waterjets. The vessel’s touchscreen controls for the port waterjets and engines also went blank.

The captain pulled back on the throttles and eventually put them in reverse to try and slow the vessel, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) said in its report on the June 5, 2021, incident. But the port engines and waterjets continued running at full ahead. Commodore ultimately veered to starboard and grounded in Bushwick Inlet, Brooklyn, at 1612.

There were seven crewmembers and 107 passengers on board at the time. One person on the ferry suffered a minor injury. Repairs to the vessel operated by New Jersey-based Seastreak cost an estimated $2.5 million.

The NTSB attributed the port-side propulsion and steering problem to a flaw in the Kongsberg Maritime Canman Touch control system software. Investigators also said Seastreak had improper safety management and training procedures for responding to a loss of propulsion and steering control.

“This (resulted) in the captain not identifying the nature of the loss of control and either engaging backup control or using emergency engine shutdowns to stop the vessel,” the NTSB said.

Seastreak does not agree with the NTSB’s conclusions and has appealed the findings, according to Jack Bevins, the company’s vice president of operations.

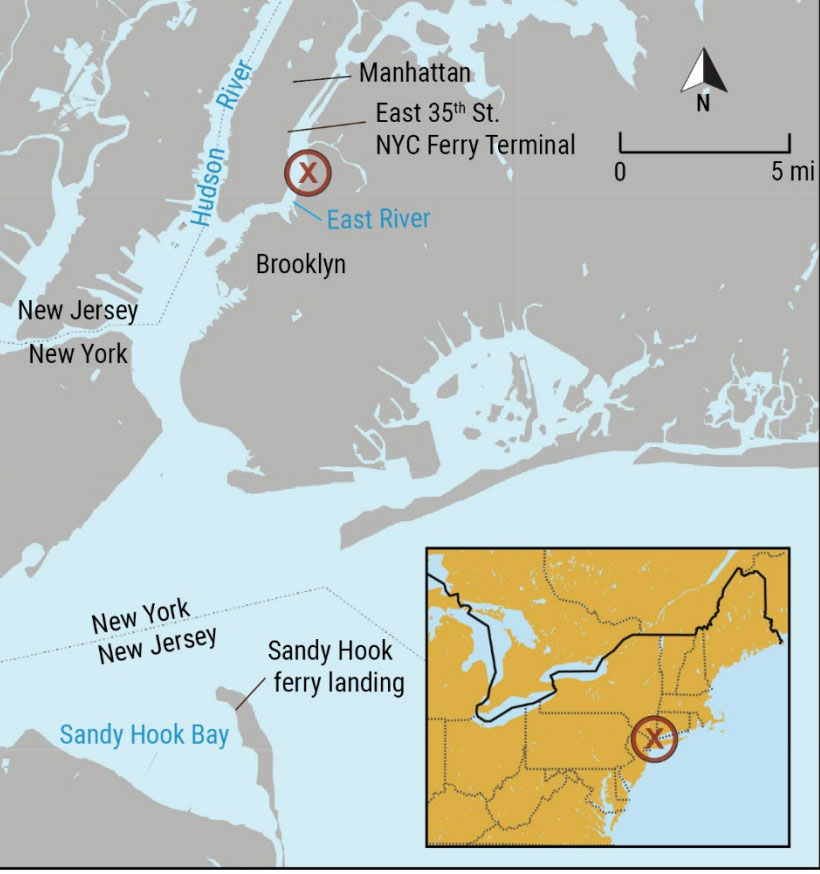

Seastreak, based in Atlantic Highlands, N.J., operates commuter ferry service between multiple New Jersey communities and two Manhattan terminals. Commodore was sailing to the East 35th Street ferry terminal from Sandy Hook, N.J., on the afternoon of the grounding.

The first sign of trouble occurred about four minutes after the 150-foot ferry passed under the Brooklyn Bridge. Alarms noted control failure in the two port waterjets, and the main touchscreen display that controlled the port waterjets went blank.

The captain tried to assess the situation at the main control console and ultimately switched to a hand control mode primarily used in harbor settings. Pulling back and ultimately reversing the engines slowed the two starboard engines but not those on the port side.

Transferring control to the port bridge wing had no effect on the control issues, and the captain’s multiple attempts to reconnect the port waterjets were not successful. Commodore turned hard to starboard into Bushwick Inlet and grounded while making about 9 knots.

Kongsberg performed a test on the touchscreen control system after the incident and found the software generated some 200,000 error messages between June 1 and June 5. This “unprecedented” number of error messages caused a critical SD memory card to fail. This SD card processed control inputs for the port and starboard waterjets.

“The failure of the main A display screen’s SD card caused the operating system to halt before starting up the controller software on that screen, causing a reboot failure, meaning that the main A display screen went blank and could not restart,” the NTSB said.

“The loss of the main A display screen also resulted in the loss of the primary controls (thrust lever, joystick and steering tiller) for the port engines and waterjets,” the report continued.

After identifying the specific cause of the mechanical failure, investigators looked at Seastreak’s safety management system (SMS) and its processes and training for responding to such an event.

For instance, there was no indication that crew recognized the vast number of error messages on the system when they started the ferry earlier that day — something the NTSB said should have been covered in the SMS. There was also no evidence that the captain tried to use a backup system to regain control of the port waterjets.

“Although Seastreak’s SMS contained information about potential responses for loss of control, it did not have procedures that clearly listed steps for the operators to follow in a time-critical loss of propulsion and steering control emergency,” the report said. “With a high-speed ferry operating at speeds in excess of 35 knots in congested waters, a quick response time is required of the operator, and clear procedures are vital to achieving a rapid response.”

The NTSB also recommended crews train for scenarios like this one that require them to respond to primary control system failures.

Kongsberg issued a service letter and software update shortly after the incident to address the potential problem. Seastreak also has updated its SMS with clear steps for the operator to regain control of the vessel during cases of loss of steering or propulsion control. •