The Soo Lock in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., is the busiest lock system in the world by cargo tonnage. It’s known as the “Linchpin of the Lakes” for its importance to Great Lakes maritime commerce.

After a lengthy wait for Congressional funding, there is now money to build a new lock chamber. Once complete, sometime around 2030, the new chamber will hopefully ease traffic and simplify maintenance on other locks at the location.

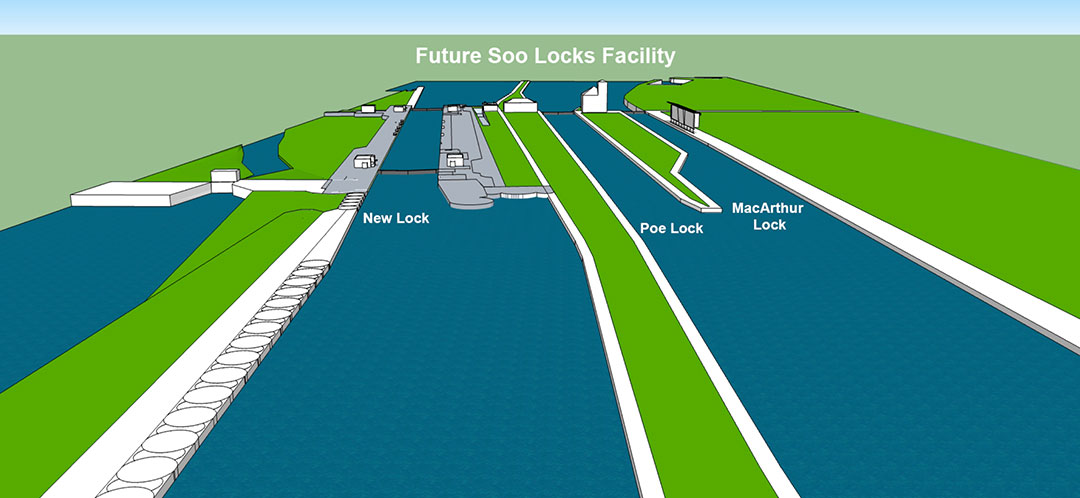

The Poe and MacArthur locks are two active lock chambers at the Soo Locks facility. The Poe Lock, built in 1969 and named for an Army officer who helped engineer the locks in the 19th century, is the only one large enough for the 1,000-foot Great Lakes freighters to traverse the locks. The larger third lock will be built in the North Canal, north of the two existing locks.

Brad Newland, a senior captain with the Interlake Steamship Company and permanent master of the 1,004-foot M/V James R. Barker, said reliability is the top issue for mariners passing through the lock system.

“Even the newest lock is getting old and while they do a good job of maintaining them, more substantial repairs simply can’t be done with the lock in service, and the possible downtime involved for a major repair could be several months,” Newland said. That’s why redundancy — having an additional large lock — is so important.

The Great Lakes shipping season typically runs from late March to mid-January when the locks close. Within that time frame, more than 7,000 vessels transit through the Soo Locks. Those vessels range from small private boats to 1,000-foot freighters carrying up to 77,000 tons of material. Iron ore, coal, grain and stone are the primary commercial cargoes.

Moving bulk cargoes through the Soo Locks and across the Great Lakes saves more than $3.9 billion each year in freight costs compared to moving the same tonnage by rail or truck. “One 1,000-foot ship can carry the equivalent of seven 100-car trains with a 10,000-ton capacity or 3,000 large trucks of 25-ton capacity each,” said Soo Locks Chief of Operations Jeff Harrington.

Originally built in 1855 to provide a passage between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, the locks have grown in size and capacity. Until about 50 years ago, the Soo Locks had been on a replacement or expansion schedule that brought better capacity about once every 18 years on average.

But something happened after 1969 when the Poe locks were completed. After that project wrapped up, the Soo seemed to be unable to garner sufficient attention and funding from Congress to keep those upgrades coming.

Going back 20 years, Newland said he has trouble pointing to any reliability issues. But in the last year or two, little problems have become more common, and he is concerned that major problems could surface at any time.

Getting to ‘yes’

Jim Weakley, president of the Lake Carriers’ Association since 2003, recalled a long process to build support for the lock expansion. For money to be appropriated for a project like this one, the cost-to-benefit ratio must be at least 1-to-1 — “but informally it is recognized to be 2.5,” he said.

As far back as the first oil crisis in the 1970s, there was talk about improving the Soo, but nothing ever happened, even when the provable cost-to-benefit ratio grew to 2.43, Weakley said. “From 1986 to 2009, the project was kept on life support through congressional earmarks, and then even those went away,” Weakley explained.

Finally, though, Homeland Security got involved. The agency declared that even a temporary closure of the major locks would result in immediate unemployment for 10 million Americans and 3.5 million Canadians. An economic validation study looking at exactly those factors was completed in 2018. That was followed by passage of the Water Resources Development Act of 2018, which included the initial authorization of $922 million for a range of projects. “The Michigan Congressional Delegation and President Trump both worked hard to pass that bill,” Weakley said.

Then, in January, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) Detroit District got a boost for the project when it was announced that it would receive $561 million in fiscal year 2022 of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (DRSAA) funds for work in Michigan and on the Great Lakes.

“The majority of money the Detroit District is receiving will fund construction of the New Lock at the Soo project,” said Kevin McDaniels, Detroit District deputy district engineer.

Nearly $479 million is slated for the Corps of Engineers’ mega-project in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., located just across the river from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. An additional $37 million is for major rehabilitation and $4 million for other existing facility work.

“The Soo Locks are nationally critical infrastructure, and their reliability is essential to U.S. manufacturing and National Security,” McDaniels said. “A failure of the Poe Lock would have significant impacts to the U.S. economy, especially the steel industry.”

Nearly all domestically produced high-strength steel used to manufacture products like automobiles and appliances is made with taconite (iron ore) that must transit the Poe Lock.

The latest round of appropriations means the project is now fully funded, he explained.

According to Kristina Schnettler, the new lock project engineer, the timeline to complete the Soo project is eight to 10 years. Construction on the project began in spring of 2020 and is scheduled to be complete in 2030, she said.

It will not only offer redundancy but much more advanced technology than existing locks, according to Schnettler. For example, the new lock at the Soo will incorporate hands-free mooring units, which are used to “grab” the vessels instead of tying the vessels off to the lock walls with lines. Four units will be required on the North wall and three units on the South wall, explained Schnettler. The new lock at the Soo is being built on the site of and replacing two inactive locks, the Davis and Sabin, and will be the same size as the Poe Lock at 1,200 feet long and 110 feet wide.

Two Countries, One Waterway

Located along a national border, the locks have always required cooperation. The U.S. and Canada work together on managing the outflows of Lake Superior through the Lake Superior International Board of Control. Furthermore, Canadian vessel captains have also been involved in design meetings with the lock users to identify any concerns with how the new lock will be constructed, Schnettler said.

With all the recent investment in the major locks coming from the U.S. side, and all the lobbying that got funding for the expansion also coming from south of the border, Weakley said flatly, “The Canadians are freeloaders.”

The Canadian side of the Soo presents a long, tangled history that doesn’t always reflect well on Americans. The first lock was built on the Canadian side in 1798 and destroyed by Americans during the war of 1812. A Canadian military expedition attempting to use the American canal in 1870 on a route to confront Canadian rebels in Manitoba was turned away, prompting a decision to construct a modern Canadian lock in 1895 — at the time one of the largest in the world and the first ever operated electrically. That structure was badly damaged a decade later when an American ship, Perry G. Walker, rammed the South Gate.

More recently, in the 1980s, that main lock suffered a wall collapse. In response, the current, much smaller lock, was built within the remains of the original 1895 structure. •