As someone who grew up listening to Supertramp, the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, it was a different experience coming up for breakfast one autumn morning to the sounds of “As I was a walking down Paradise Street, way, hey, blow the man down” reverberating through the kitchen.

There was my dad, who sailed for years as an able seaman and boatswain, drinking his coffee and singing along with the English sailors who recorded the song. While I poured milk over my bowl of Cap’n Crunch I must have looked at him strangely, because he gruffly asked, “What’s the matter with you son, never heard a sea shanty before?”

Sea shanties like “Blow the Man Down,” were not the first use of songs and singing onboard vessels. According to the National Maritime Historical Society, for centuries the ancient Greeks, Vikings and Chinese all had musicians and sang on board to keep the oarsmen rowing in unison. In fact, ancient Egyptian drawings discovered in Giza show a musician with a flute-like instrument on the bow as the oarsman rowed. Greek Triremes had both oars and sails, and they carried over 200 crewmen who sang to keep in unison. One of their rhythmic chants, the “Ri-Pa-Pe,” has been verified by historians and is believed to be over 2,500 years old.

By the 1800s, shanties like “Haul Away, Joe,” and “Paddy Doyle’s Boots” were standards on board European and British sailing ships. Considered a genre of folk song, they had a rhythmical beat, and were used on merchant sailing vessels to keep the deck gang synchronized while handling lines to raise and lower the sails or anchor. The first mention of sea shanties in modern literature was in British Author G.E Clark’s 1867 classic “7 Years of a Sailor’s Life,” which described the importance of songs like “We’re Homeward Bound” onboard a ship.

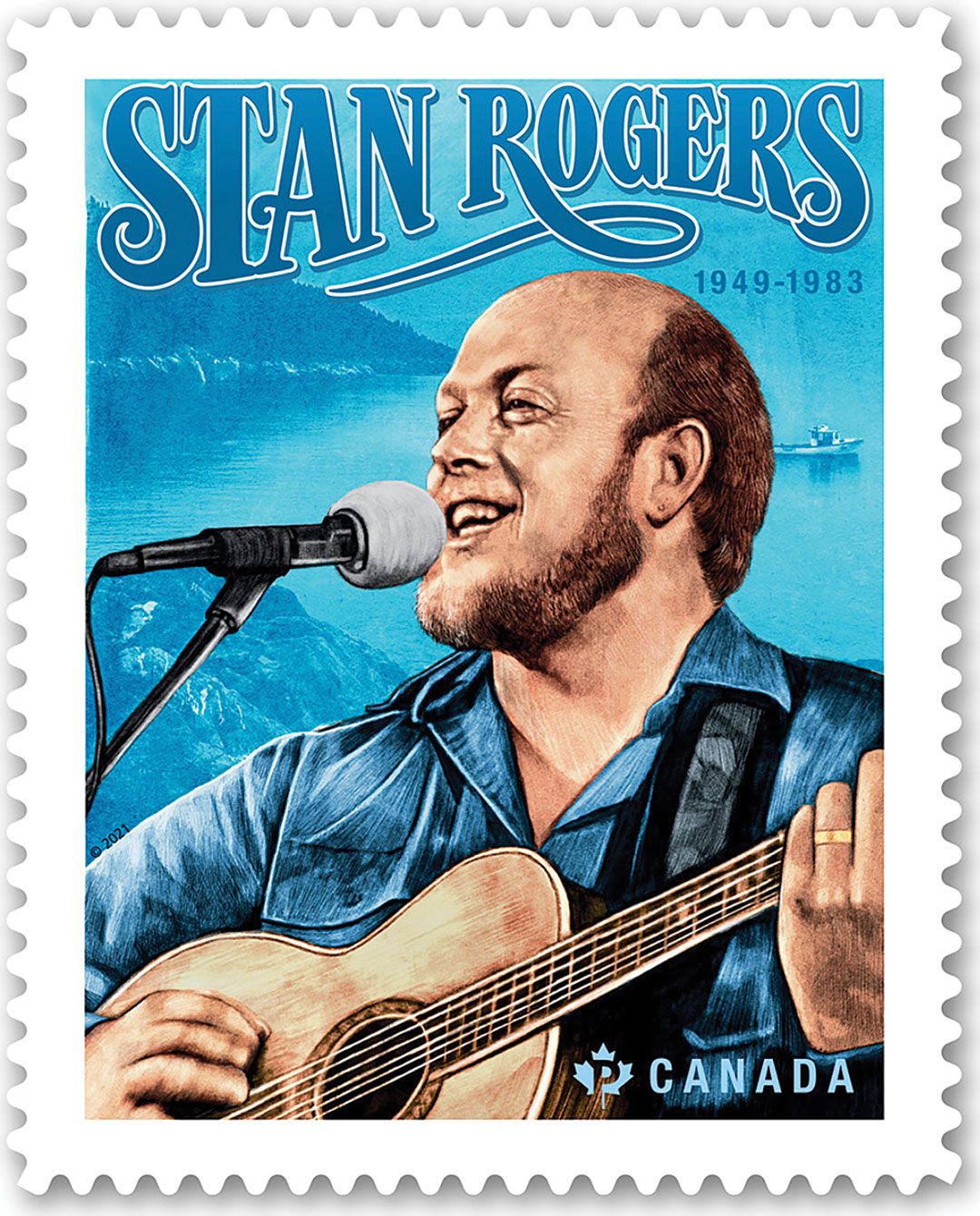

Around 1920, machines replaced the manual labor of the sailing ship era, so sea shanties on working ships essentially became a thing of the past. Possibly it was nostalgia, but by the mid-1930s the public became attracted to them. Popeye’s signature song “I’m Popeye the Sailor Man” came out around then, introducing a new generation to sea shanties. Decades later they are still popular. Johnny Depp’s original “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie had shanties such as the famous “Yo Ho, Yo Ho, a Pirate’s Life for Me.” Musicians like Stan Rogers and Great Big Sea have made a good living singing them.

What’s interesting to me as a mariner, however, is not just the staying power of sea shanties but how many songs about the sea there are in popular music. One example is the bestselling hit by Canadian singer/songwriter Gordon Lightfoot, whose iconic “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” from the late 1970s describes the 29 crewmembers’ last moments on its ill-fated voyage. I have sailed with mariners who worked on the Lakes. They told me his song keeps alive the memory of those who died in the tragedy. They also remind the public of the trials mariners can face. Being from Faribault, Minn., and getting his start in the merchant marine on the Lakes himself, my old salt father would tear up when he heard it.

People who don’t work on or near the ocean may not realize its importance, but songs of the sea can bring it to them. Jimmy Buffett’s “Son of Son of a Sailor” details his family’s sea-going experiences over three generations, and his “Captain and the Kid” talks about how his grandfather instilled his love of the sea. The Beach Boys’ “Sail on Sailor” emphasizes that even in “gale-swept seaways” we all must continue on. Crosby Stills and Nash’s “Southern Cross” is probably my favorite of this genre because it describes some of my own experiences. That song drifted through my mind the first time I saw the real Southern Cross in the night sky.

Although each of these songs may have different personal meanings, their use of maritime phrases, terms, ideas and titles have helped in some way to connect, consciously or unconsciously, millions of listeners to mariners, the ocean, and the vessels that ride the waves. And though I admit to still listening to Supertramp, the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, at sea or ashore I will put a nautical song on, too. Today it was Lightfoot’s Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. And like my dad before me, by the end of the song I too had tears in my eyes.

Till next time, I wish you all smooth sailin.’

Capt. Kelly Sweeney holds the license of master (oceans, any gross tons) and has held a master of towing vessels (oceans) license as well. He has sailed on more than 40 commercial vessels and lives on an island near Seattle. He can be contacted by email at captsweeney@outlook.com