with Alanis.

The hydrodynamic forces known as bank cushion and bank suction were leading factors in the collision between Florence Spirit and Alanis in Welland Canal in 2020, Canadian authorities have determined.

Inadequate communication between the master on the Canada-flagged Florence Spirit and the pilot conning the Antigua and Barbuda-flagged Alanis increased the complexity of the meeting and contributed to the collision, according to Canada’s Transportation Safety Board (TSB).

The two ships collided while meeting near mile 16 in the Ontario, Canada, waterway on July 11, 2020. Nobody was hurt and there was no pollution but both ships sustained damage above the waterline.

Videos of the incident available online show a slow-motion collision developing as the downbound Florence Spirit sheers to port and enters the sea lane occupied by the upbound Alanis. Recordings captured the long metallic roar of hull against hull as their bows slid together, starboard to starboard.

“Florence Spirit proceeded into the meeting at the maximum permissible speed of 9.9 knots, which increased the hydrodynamic forces acting on the vessel and reduced the ability to maintain steering control,” the TSB said in a news release.

“The hydrodynamic forces generated, combined with the proximity of the bank, produced a yawing moment such that the vessel yawed uncontrollably to port into the path of Alanis and collided with it.”

The 453-foot Alanis, operated by dShip Carriers, carried wind turbine parts bound for Duluth, Minn. McKeil Marine of Burlington, Ontario, operated the 447-foot Florence Spirit, which carried coal bound for Quebec City. Neither company responded to inquiries about the TSB findings.

The master on Florence Spirit was training under another piloting master who held a Great Lakes Pilotage Authority certificate to operate ships in areas where pilots are required. The ship’s master was on his 12th of 15 voyages required to obtain his certificate.

Meanwhile, the master on Florence Spirit had previously worked with the pilot conning Alanis, who had been his supervisor. The two traded messages to discuss the meeting in a section of the canal known as the Welland Bypass. Florence Spirit’s master used his cellphone to send text messages, while the pilot on Alanis used his portable pilot unit (PPU).

“The initial message, sent by the pilot, indicated that the master had full discretion to select whatever speed and maneuvers he felt appropriate for the upcoming meeting,” the TSB said in its report.

“The pilot indicated to the master that wide-beam loaded vessels like Florence Spirit will move sideways in the lock if too much propulsion is applied,” the report went on. “The master then indicated that he would increase Florence Spirit’s speed once past Ramey’s Bend, and the pilot indicated that Alanis was proceeding slowly.”

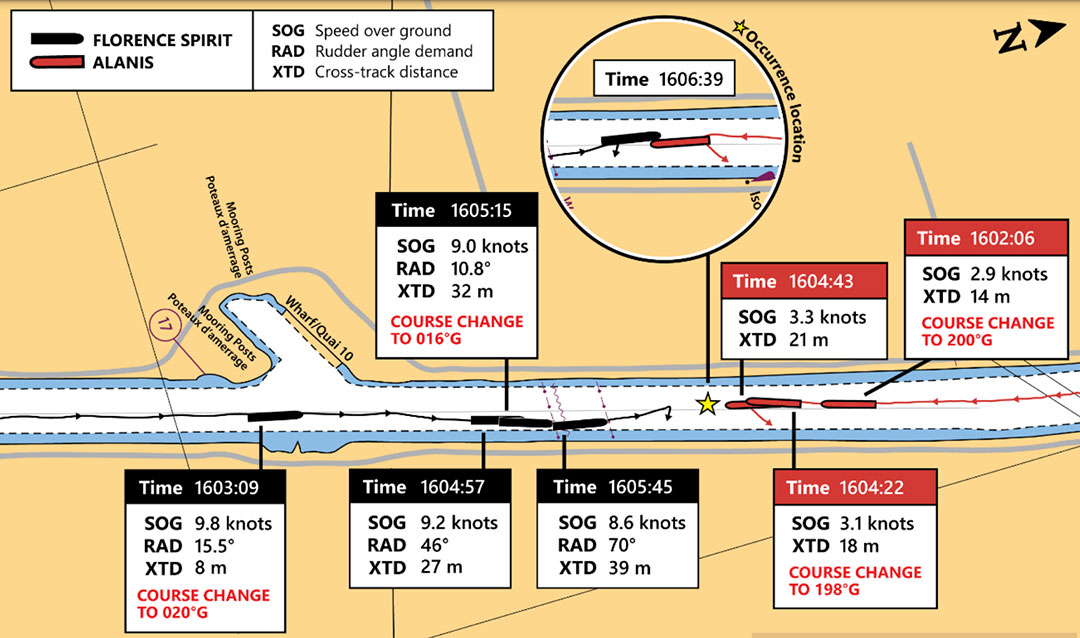

Florence Spirit entered the Welland Bypass at 1543, and over the next few minutes its master and the pilot aboard Alanis communicated several more times via message. At about 1605, Florence Spirit struggled to maintain its course alongside the bank. As the piloting master warned of bank forces, the ship suddenly sheered to port toward the downbound Alanis.

Despite efforts by its crew to regain control, the ship continued into Alanis’ path. The two vessels collided at 1606. Florence Spirit was making about 6 knots, while Alanis was proceeding at about 3 knots in the moments before the collision.

Bank cushion and bank suction are the two primary bank effects that can impact a ship. According to the TSB, bank cushion affects the bow while bank suction impacts the stern. Mariners try to avoid these forces by staying as close to the center of the channel until the approaching vessel is less than a mile away, at which point both ships will begin edging to starboard for the meeting.

Bank cushion and bank suction are the two primary bank effects that can impact a ship. According to the TSB, bank cushion affects the bow while bank suction impacts the stern. Mariners try to avoid these forces by staying as close to the center of the channel until the approaching vessel is less than a mile away, at which point both ships will begin edging to starboard for the meeting.

“A common strategy during meetings involving larger vessels is for the vessels to mirror each other’s speeds and course alterations in order to leverage the repulsive forces generated between them to counteract sheer and compensate for bank effect,” the TSB said.

Based on the informal communication between the two mariners, the master aboard Florence Spirit misunderstood how fast his ship should travel. While the Alanis pilot expected the ship would approach at 6 or 7 knots, Florence Spirit’s master believed he could transit at the maximum allowable speed of 9.9 knots.

Florence Spirit’s speed increased the hydrodynamic forces acting on its hull and reduced its crew’s ability to control the ship, the TSB said.

“This interpretation of the pilot’s message gave the piloting master the impression that the meeting could be conducted successfully at this speed, and the fact that the message was coming from a licensed pilot added credibility to it,” according to the report.

Following its own internal investigation, McKeil Marine issued a fleet advisory on bank effect and bridge conduct, held a pilotage trainer meeting to review bridge conduct, added a training module on bank effect to its Great Lakes Marine Pilotage Certificate Training Program and modified other modules to include more guidance on the dynamics between the trainer and trainee.

It also conducted rudder timing and efficiency tests on company vessels and updated the vessels’ maneuvering characteristics posted on the bridge, ensured that new and upcoming masters took ship-handling simulator training, and required piloting mates to complete additional training in a simulator.

McKeil also required the master at the time of the incident to complete two sessions of simulator training and extended the number of training trips that he was required to complete in the Welland Canal to 25.

Following the collision, the Great Lakes Pilotage Authority implemented a process requiring restrictions to be placed on newly issued pilotage certificates related to vessel size, vessel type, company of operation, geographic area, and capacity limitations on the candidate’s certificate of competency. It also prohibited the use of electronic devices while employees are engaged in pilotage duties on the bridge of a vessel.