In December 1976, Capt. Georgios Papadopoulos commanded Argo Merchant on a venture beginning at Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela. The destination was Salem, Mass., where the tanker was scheduled to deliver a winter's supply of home heating fuel. The 18,743-ton, 644-foot ship was loaded with a cargo of 7.7 million gallons.

Personnel and mechanical problems, complicated by bad weather, resulted in the demise of Argo Merchant on Dec. 15. The ship was carrying an unqualified helmsman on board, and it was later reported that this crewmember had not been properly supervised in the hours immediately before the emergency. No accurate celestial fix had been obtained for at least 15 hours before the accident. The captain also indicated at an inquiry that the tanker had a malfunctioning gyrocompass.

|

|

|

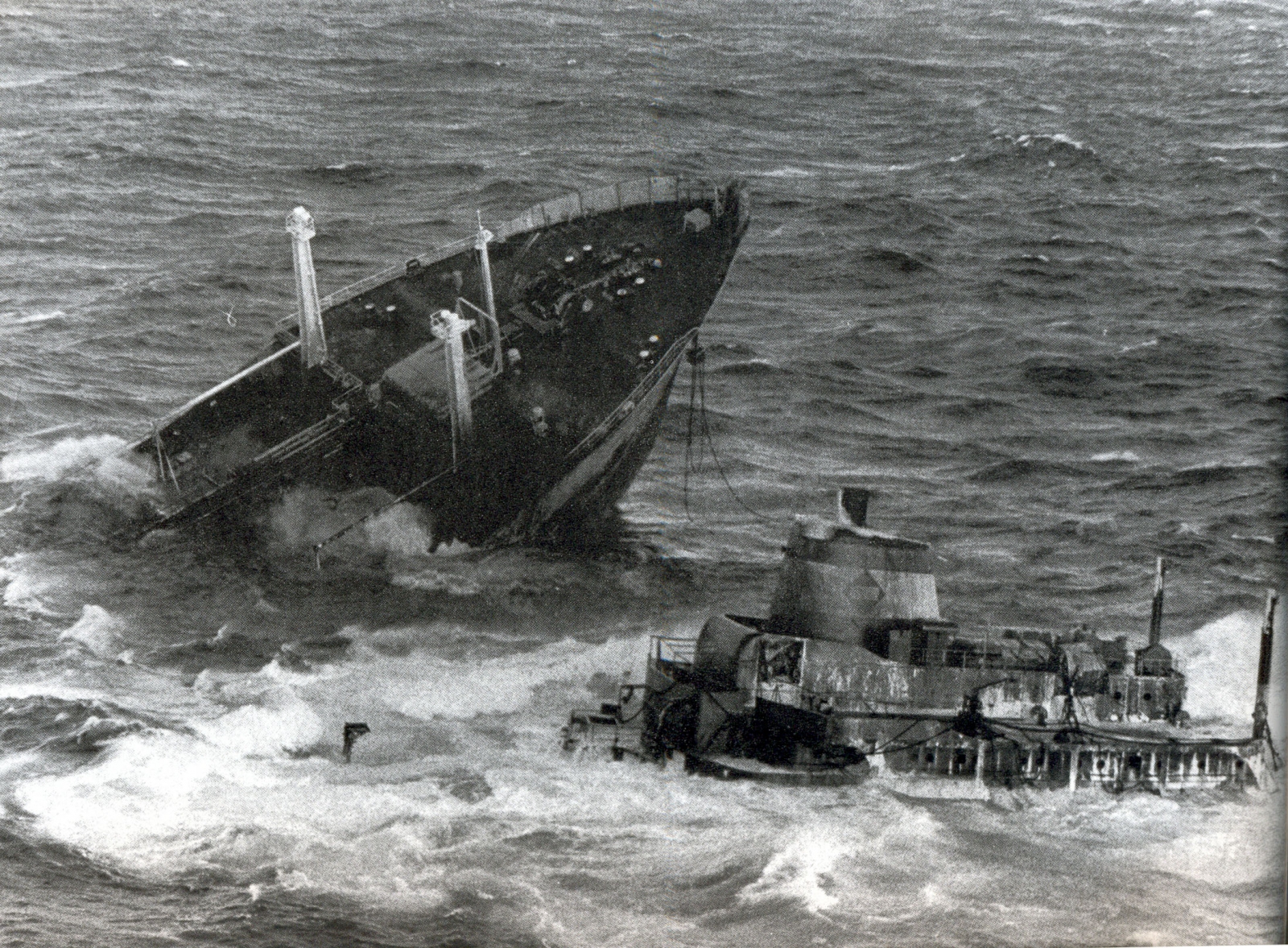

Heavy seas cover the decks of Argo Merchant while the tanker lies aground near Nantucket Island. The ship was carrying 7.7 million gallons of home heating fuel when it went off course and became stuck on Dec. 15, 1976. (Photos courtesy U.S. Coast Guard) |

These problems came to an unfortunate confluence when the weather turned bad. A winter storm generated high winds and 10-foot seas, driving them across the bow of Argo Merchant, causing the ship to run aground on Middle Rip Shoal in position 41° 2' N, 69° 27' W – about 25 nautical miles southeast of Nantucket, more than 24 miles off course.

The captain, fearing destruction of the ship in rough conditions, requested permission to dump cargo in an effort to refloat the vessel. No permission was forthcoming from the salvage company responsible for the value of the cargo. Other methods of minimizing damage by attempting to make the ship lighter, e.g., emergency pumps and an Air Deliverable Anti-Pollution Transfer System (ADAPTS) failed because of weather conditions and shallow waters. It had been hoped emergency measures would reduce stress on the frame and keep the distressed tanker from breaking apart until the oil could be offloaded.

Instead, Argo Merchant remained heavily laden and inflexible in the turbulent water. It became clear her structure was threatened as tug assistance failed and the weather continued to deteriorate. Consequently, the captain made the decision to evacuate on Dec. 16. In response to this request and to worsening conditions, the U.S. Coast Guard, operating out of the Coast Guard air station on Cape Cod, Mass., dispatched helicopters to rescue the 38-man crew.

|

|

|

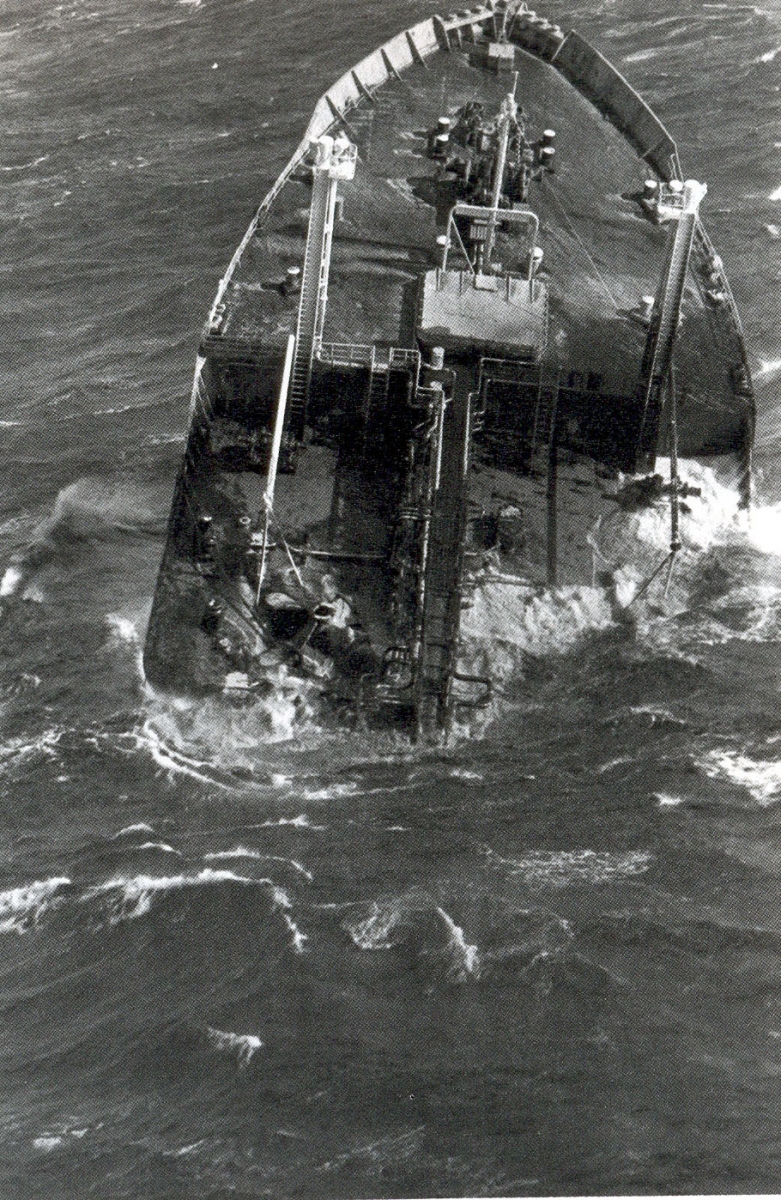

After its crew evacuated, Argo Merchant broke apart and spilled its cargo of heating fuel. |

On Dec. 17, Argo Merchant rotated and buckled. Four days later, the ship broke in two, spilling its cargo. The bow section split forward of the bridge and capsized the next day, floating aimlessly a few hundred yards to the southeast. Eventually the Coast Guard sank the bow section, but the stern section remained aground.

Attempts to prevent environmental damage were ineffective. Emergency crews twice tried to burn Argo Merchant on site. On Dec. 27 they used boxes of water resistant, flammable material charged with jet fuel (Tullanox), dropped by helicopter onto the ship. On this first attempt, the boxes were ignited using timed grenades. The boxes themselves burned, but the fire did not spread as hoped.

The second attempt, this time on a large slick, was conducted on Dec. 31. The Coast Guard vessel Spar, aided by aircraft, located a large, oval-shaped area of oil which broke into smaller circular patterns as the salvage boat approached and moved into position. More Tullanox was dropped onto the oil in the form of open bags. None of these efforts were successful, and the entire endeavor was terminated after failing to maintain a sustained burn.

Pancake-shaped slicks of almost 200,000 square feet developed. These slicks were, in some cases, 10 inches thick. The next spring, oil balls weighing as much as 70 pounds washed ashore on Nantucket. Analysis of the oil confirmed it was identical to the cargo carried by Argo Merchant. It could not be definitively determined, however, that these particular balls were part of her load. Sediment samples taken in the area of the spill consistently showed oil contamination.

|

|

|

The tanker's bow section remained afloat for some time after breaking off, until the Coast Guard purposely sank it. |

It was fortunate that northwesterly winds prevailing at the time spared coastal areas, fisheries and beaches by blowing the oil offshore. Because of the direction in which the wind blew the oil, concern about damage focused on economically important fishing grounds in the area of Georges Bank. Evidence of oil contamination was observed in fish, shellfish and plankton collected in that area. Cod and pollack eggs were also contaminated. Seabirds, especially gulls, were fouled with oil, mostly on the breasts and abdomens. Diving birds reportedly fared better, few being observed heavily oiled.

The local populace was concerned about the Argo Merchant spill and media coverage kept the accident visible. Information was often wildly inaccurate, giving the impression that there had been widespread, serious damage. It took consolidation of two salvage team command posts to alleviate the problem of conflicting information, and careful tracking of the spill as it moved away from land, to assure the public that no permanent damage had been done and minimal short-term damage had occurred.

Because of the public scrutiny, the Argo Merchant accident was the focus of intense scientific activity for several months after the grounding. Ecological impact was assessed by studying migration of the oil, as well as the flora and fauna affected. Research vessels from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution performed special operations to determine the magnitude and progression of the spill itself. Government agencies, including the Coast Guard, NOAA, the U.S. Geological Survey and others collected numerous water, sediment, fish and shellfish samples.

Thorough efforts were made to observe and track the oil. Attention was paid to mapping the spill in order to allay environmental concerns and to develop models for the future. It was determined that the spill traveled at an average speed of just over 1 percent of surface wind speed. Six thousand drift cards were positioned between the spill and the shore designed to give advance warning at locations of probable coastal contamination.

After some early confusion concerning roles of the various agencies involved, research efforts were well coordinated and, as a result, very successful. The findings provided assurance to the public that minimal ecological damage had been done as a result of the Argo Merchant spill.

An indication of the relatively small amount of damage done to area fowl could be seen in the number of birds recovered. Only 160 oiled birds were located.

As a direct result of this disaster, NOAA developed a hazardous materials team to provide and coordinate future responses, funnel necessary information to the Coast Guard, and to develop standard methods of assessing oil spills. This team has grown in the years since Argo Merchant, with expert personnel located around the United States.